All-wheel drive (AWD/4WD): pros, cons, problems

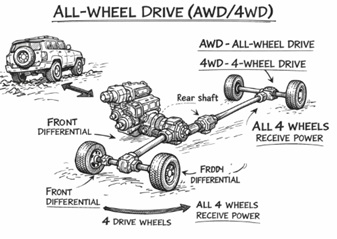

All-wheel drive (AWD/4WD) is a drivetrain layout in which driving torque is distributed to all four wheels, with the goal of increasing traction and stability across a wide range of grip conditions.

The main advantage is the ability to exploit more tire contact patches: by spreading torque over two axles, each wheel carries a lower traction demand, reducing the likelihood of wheelspin and improving launch and pull on slippery surfaces.

From an architectural standpoint, AWD requires a link between the front and rear axles via a torque-splitting element: this can be a center differential (with fixed or variable split), an electronically controlled multi-plate clutch, or an electronically controlled coupling. In more off-road-oriented solutions, a transfer case is used and, in some cases, a low range is available.

A key aspect is how speed differences between axles in a turn are managed. Systems with a center differential allow rotational differences without driveline stress and are suitable for continuous use on dry pavement. Systems without a center differential (a “locked” 4WD) require low-grip surfaces to avoid wind-up and mechanical strain.

Torque split can be symmetric (e.g., 50:50) or biased (e.g., front- or rear-heavy), and in modern systems it is often variable in real time. Control strategies can be reactive (intervening after slip begins) or predictive, preloading the system based on torque demand, steering angle, accelerations, and detected conditions.

AWD interacts closely with stability electronics: TCS and ESP manage wheelspin and vehicle attitude, using selective braking and torque control to improve traction and stability. On many platforms, brake-based interventions can also simulate a limited-slip differential on an axle, helping route torque to the wheel with more grip.

From a dynamics perspective, AWD can increase exit speed and stability under acceleration, but it does not remove the physical limits of grip: if entry speed is too high or grip is extremely low, loss of control remains possible. Moreover, the balance (understeer/oversteer) depends on calibration, tires, and torque distribution.

The main trade-offs are weight, parasitic losses, and complexity: additional mechanical components (shafts, joints, differentials, clutches, actuators) increase mass and cost, and can worsen fuel consumption compared with 2WD. Maintenance may include specific fluids for differentials/transfer case and, in some systems, actuator checks or calibrations.

From an application standpoint, AWD is especially beneficial in cold climates, on wet or snowy roads, on unpaved surfaces, and for high-torque vehicles, where distributing power across four wheels improves the ability to put torque down effectively. It is also advantageous for towing and on steep ramps because it reduces traction losses.

In summary, all-wheel drive increases traction and stability by distributing torque to four wheels, delivering superior performance on low-grip surfaces and under acceleration. However, it comes with higher weight and complexity, and it remains constrained by physics: tires, available grip, and speed are still decisive for safety.

![]() All-wheel drive (AWD/4WD)

All-wheel drive (AWD/4WD)