Selectable all-wheel drive: pros, cons, problems

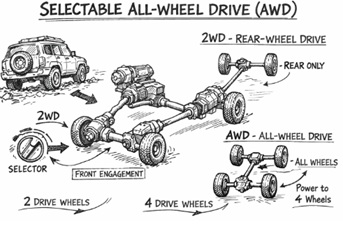

Selectable all-wheel drive is a drivetrain solution in which the vehicle normally operates in 2WD (two driven wheels) and can switch to 4WD/AWD (four driven wheels) via a driver command or an automatic logic, with the goal of increasing traction on low-grip surfaces.

The principle is torque distribution across two axles: under standard conditions the system prioritizes efficiency (lower parasitic losses, fuel consumption, and wear) by driving only one axle; when extra traction is needed, a mechanical connection between the primary and secondary axles is engaged, reducing wheelspin risk and improving the ability to move forward.

From a hardware standpoint, the core element is the coupling device: it can be an electronically or electro-hydraulically controlled multi-plate clutch, an electronically controlled coupling, or (in more traditional layouts) a transfer unit with a rigid engagement. Many vehicles also use a transfer case to manage torque distribution and, in off-road applications, it may include a low range.

The operating strategy can be manual (2WD/4WD selection via button or lever) or automatic: in the latter case a control unit evaluates inputs such as wheel speeds, accelerator position, requested torque, steering angle, and sometimes yaw rate, and progressively engages the secondary axle when it detects traction loss or predicts critical conditions.

A fundamental technical aspect is the presence or absence of a center differential. Many road-oriented selectable AWD systems use a clutch/coupling that allows controlled slip between axles, so they can operate on dry pavement without excessive driveline stress. By contrast, rigid engagement systems (without a center differential) should be used only on slippery surfaces, because on dry pavement they generate driveline “wind-up” (torsional stress build-up), with wear, noise, and potential damage.

Torque split can be fixed (for example 50:50 in a locked mode) or variable: multi-plate clutch systems modulate clamp force to transfer more or less torque to the secondary axle, delivering smoother behavior and better on-road compatibility. In more advanced systems, the logic can also be predictive, preloading the coupling before obvious wheelspin occurs to reduce response time.

From a vehicle-dynamics standpoint, engaging AWD influences stability: it increases traction under acceleration, but it can also change the balance between understeer and oversteer depending on tires, torque split, and electronic controls. For this reason, selectable AWD often works together with ABS, TCS, and ESP, which manage selective braking and torque control to keep the vehicle within a stable operating window.

Practical benefits are clear on snow, mud, gravel, wet grass, and steep ramps: better launch capability, fewer traction breaks, and more consistent progress. In some conditions it also reduces “aggressive” traction-control intervention because torque is spread across more tires.

Limitations relate to complexity and maintenance: more components (clutches/couplings, actuators, sensors) mean more potential wear points and the need for specific lubricants and periodic checks (transfer-case/differential oil, calibrations). Incorrect use of a rigid 4WD mode on dry pavement is also a common cause of mechanical issues.

In summary, selectable all-wheel drive is a technical compromise between efficiency and traction capability: it allows 2WD operation when extra traction is not needed and enables 4WD/AWD when conditions require it—provided the system’s constraints are respected (especially the presence or absence of a center differential) and driving inputs remain consistent with available grip.

![]() Selectable all-wheel drive

Selectable all-wheel drive